The G20 Summit is likely to generate many headlines and few concrete measures. However: Read More

The G20 Summit is likely to generate many headlines and few concrete measures. However: Read More

There is absolutely no need for a rate cut.

Consumer confidence is high, unemployment is low and Treasuries’ yield is at 2.1%, while credit to the economy and corporate financing are not suffering.

The weakness in core consumer prices in May, which increased by only 0.1 %, was entirely due to lower prices of used vehicles, and core CPI inflation remains within the Fed target, falling from 2.4% in mid-2018 to 2.0% in May. Headline CPI inflation fell to 1.8% in May due to lower energy prices, so there is absolutely no logic in a rate cut. With unemployment at 3.6%and annualized GDP growth expected to remain above 2.3%, demands for a rate cut are only an excuse to keep financial asset prices higher at any cost

There are some elements that point to a slight weakness in the economy but no need for a rate cut.

A rate cut would only fuel the debt bubble further, and leave the Fed with fewer tools to address a slowdown. When so-called “High Yield” means 365 bps for junk bonds of companies close to bankruptcy and Treasuries yield 2.1% there is no reason at all to cut rates. Rather the opposite.

The debt bubble is dangerously inflated and lower rates would only make it worse. The ratio of US corporate debt to GDP, as well as the high-risk loan figure and securitized debt, have risen to pre-crisis levels. US deficit is rising because spending soars and the government finds debt cheap and abundant. Government spending rose to $440 billion in May 2019, up 21% from May of 2018. Yes, up 21% from May of 2018. All this despite record revenues. Receipts increased to $232 billion, up 7% from the same month last year.

A rate cut would only create a larger problem in the future. If the already dangerous corporate and sovereign debt bubble grow significantly more, no monetary policy will prevent a debt crisis.

In these weeks we have read a lot about the so-called trade war. However, this is better described as a negotiation between the largest consumer and the largest supplier with important political and even moral ramifications. This is also a dispute between two economic models.

Nobody wins in a trade war, and tariffs are always a bad idea, but let’s not forget that they are just a weapon. Read More

In this fifth episode of my video-blog, we discuss the mistake of believing GDP as the key driver of economic growth, as it is not difficult to inflate via debt.

We also discuss the differences between the US, China and EU, and why the slowdown in the Eurozone should concern us more.

In this fourth episode of my video blog, I explain the economic slowdown, why central banks are not understanding the key global trends and what they mean for inflation, growth and productivity.

Do not miss the other episodes. Thanks for watching!!

Third Episode of my video-blog World Economics. Thanks for the success of the other episodes. This month we speak of the global slowdown and the poisoned solution of more stimuli and “a new deal”

What happens when politicians see that their monster stimuli have not delivered? They bring the next rabbit out of a hat. They need a new name and a new magic solution to make citizens believe in the magic of demand-side policies despite the constant failure of those same plans. Read More

Talking in CNBC about the 2019 outlook

The central idea is that we are in the process of a change of cycle that central banks and governments are unlikely to disguise because both monetary tools and fiscal space have been exhausted. This change of cycle may not lead to a 2008-style recession, but more likely to a Japanese-style stagnation as debt continues to rise while economic and productivity growth weaken. As such, we as investors may believe the mirage of a chain of “bullish” headlines in the first part of 2019: a trade deal between the U.S. and China (likely), a large China stimulus (very likely) and central banks’ relative dovishness (highly likely). This may create short-term bounces, but the euphoria effect many quickly fade because even with a bounce in global liquidity, net financing needs may exceed real growth. If markets react quickly and aggressively to these “false” bullish signals increasing risk and leverage, the probability of falling into a 2008-style crisis increases. Liquidity is falling, and this may reduce this risk of abnormal bullishness.

The G20 meeting in Buenos Aires had a primary objective. To reach an agreement between the United States and China.

However, the announced agreement is more a “diplomatic truce” than a real agreement.

The United States commits to delaying tariffs against China that would start on January 1st, 2019 and China commits to purchase more agricultural and energy products (LNG, liquefied natural gas) in addition to promising to advance in legal security, compliance with contracts, the opening of capital markets and protection of intellectual property.

However, the wording is vague, the commitments are conditional and the time is limited.

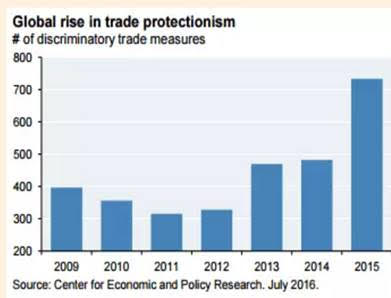

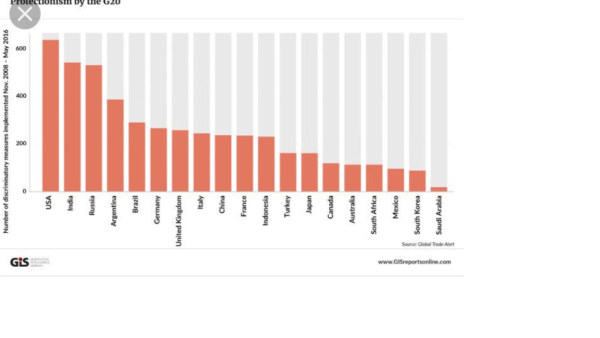

When we talk about trade wars as if they were something new, we make a diagnosis mistake. We’ve been in a trade war for years. The United States has been denouncing trade barriers imposed by China and other countries directly and indirectly for years, with a World Trade Organization that did nothing about it.

The United States acted in the wrong way, and between 2009 and 2016 introduced more protectionist measures than any other G-20 country. The World Trade Organization warned on several occasions before the Trump administration took office of the increase in protectionism since 2011.

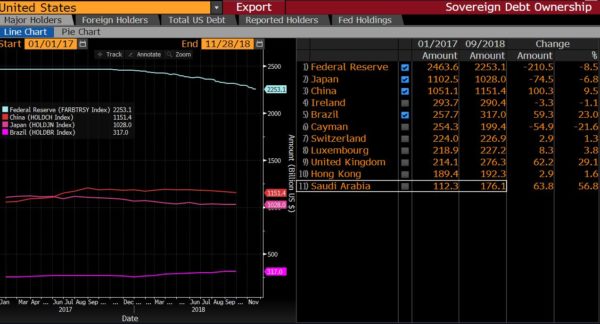

China desperately needs to keep the trade surplus with the United States to maintain its extremely indebted growth model. More than the United States needs China to purchase its debt.

China is not the main holder of US bonds (not even the largest foreign buyer). The largest holders are North American institutions and investors in their vast majority.

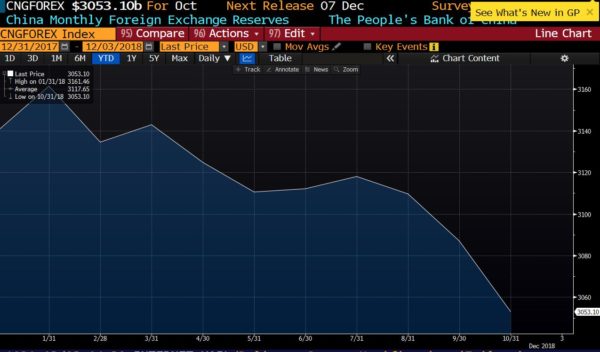

The United States has seen demand for its bonds remain robust and yields have not soared even with China and the Fed selling. Meanwhile, China’s foreign exchange reserves have fallen.

China’s foreign currency reserves fell to the lowest level in 18 months in October. A reduction of $ 33.9 billion in October, the worst since December 2016 and the lowest level since April 2017.

China cannot maintain its growth – based on a huge debt bubble – if its exports to the US fall. There is no other market that can offset its exports to North America. And its trade surplus with the United States is already over 275 billion dollars per year, the biggest contributor to the Chinese GDP from the external sector.

A drop in the growth of China’s exports would mean a much larger collapse of its foreign exchange reserves, which are down 30% since the 2014 highs.

A collapse in foreign exchange reserves also accentuates the already existing capital flights, which in turn would lead to more capital controls and, with it, three effects. Lower growth, an increase in the already high debt and the risk of a very important devaluation of the yuan.

These three effects have already happened in 2018.

In summary, for China, the trade war is devastating. For the US it is negative, but for China it is a disaster.

The United States exports very little (11% of GDP), so any threat that leads to an agreement is good.

A trade war can generate higher costs of goods and services for Americans, but the reality is that China exports disinflation and, if any, inflation expectations are falling, not rising.

This does not mean I support trade wars. It means that the idea that both sides are equally negatively impacted is simply empirically incorrect.

As such, the agreement announced between the US and China in the G20 is nothing more than a “conditional ceasefire”.

China has little intention of guaranteeing intellectual property and eliminating capital controls or the immense interference between political and legal power.

The increase in purchases from China to the United States announced is likely to have a very low impact on the trade surplus . China’s trade surplus with the US has skyrocketed in 2018 from 21.9 billion dollars in January to 34.1 billion in September. If China doubles its purchases of agricultural and energy products from the United States, something very difficult to achieve, this surplus would only fall by a maximum figure of 3 billion US dollars.

This agreement is only a pause, and the announced tariffs would be recovered if improvements are not evident. The tariffs announced for January 1st would be increased to 25% if China does not comply in 90 days.

The differences in the interpretation of the agreement between the Chinese and US administrations can be seen in their official statements.

While the US says that China will change its policy with respect to intellectual property, capital control and legal security, China only says that they “will work together”. While the US states that the agreement is invalidated after 90 days, China does not mention the deadline. While the US mentions that the purchases of North American products will increase in specific sectors, China only talks about buying more products.

This agreement does not change the trade and policy differences of both countries, but it is very similar to the failed agreement reached with China in May that ended in nothing. We have to be very cautious and wait to see if real economic data improves. If China continues to devalue the Yuan and inject capital into its financial and corporate sectors it will be a sign that the agreement has no credibility for the Chinese government itself. Furthermore, as leading indicators show, the global slowdown is much deeper and complex than the differences between China and the US on trade. If the global economy recovered the trade growth levels of 201, global GDP slowdown would still be evident, and more pronounced than consensus currently estimates.

This trade deal is not only vague, conditional and temporary… It does not disguise the slowdown of major economies, which had nothing to do with trade wars and a lot to do with debt saturation.

Be careful thinking that this is a catalyst that puts the world back in growth and multiple expansion modes. The reality is that this deal is not a catalyst for the global economy.