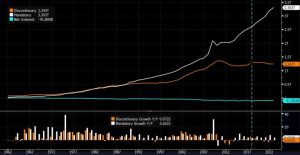

The United States recovered 4.8 million jobs in June, adding to May’s 2.5 million jobs rebound. The United States employment recovery is faster and stronger than the Eurozone one, which has over 40 million workers on subsidized jobless schemes added to a 7.4% unemployment that is expected to rise to 11% by September.

However, the positive headlines show important weaknesses that will have to be addressed in the following months. Labor Department data showed that in the week ending 27 June, initial claims for unemployment fell only slightly, to 1.43 million, on the previous week. Additionally, continuing claims remained stubbornly high at 19.29 million and the share of those reporting permanent job losses increased by 588 thousand.

Considering these factors, the trend shows that the United States unemployment rate would fall to 8.5% with a labor force participation rate of 63% at the end of 2020, according to my estimates. Goldman Sachs has improved its unemployment rate outlook to 9% for 2020 from 9.5% a month ago. However, at this rate the United States would only recover the 2019 record-low unemployment at the end of 2021. Still, much faster than the eurozone.

Subsidized jobless schemes, as the eurozone economies are implementing, is costly and generates extraordinarily little impact on consumption. Government spending is rising at the fastest pace in decades to include the increase in healthcare costs, the jobless insurance expenses, and the subsidised jobless programs. However, workers under these schemes know that their positions are at risk and are deciding, wisely, to save as much as they can. Almost 10% of the labor force in the major European economies is under one of these schemes, designed to help businesses navigate the crisis without letting go of employees.

The World Labor Organization estimates that 400 million full-time jobs have been lost in this crisis. Recovering and strengthening the labor market is crucial for developed economies to achieve the estimates of gross domestic product growth expected in 2021 and 2022. Without a strong job market, consumption and growth are likely to stall in 2021, and it will be exceedingly difficult to see investment growth.

How can economies recover the lost employment and continue to create jobs? Unfortunately, many governments would have to do the opposite of what most developed economies are doing. They should stop bailing out zombie firms, as those already had overcapacity in the past five years and are not going to hire more workers soon. Governments should also reduce unnecessary spending to prevent deficits from rising to unmanageable levels and then increase taxes that would reduce investment and job creation. Bloated public budgets are not going to bring employment back. It did not work in the eurozone in the 2009-2012 period and it will not work elsewhere.

The United States government has taken a more effective approach by combining some demand-side measures with more efficient supply-side policies that have supported the job recovery, even if it is still weak. There is a long and painful road ahead, and the rising number of covid-19 cases may harm the economic recovery as lockdown risks return.

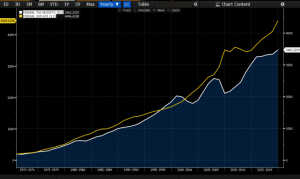

Some commentators in Europe have argued that the job recovery in the United States is stronger due to a larger fiscal and monetary stimulus. It could not be further from the truth. The European Central Bank balance sheet is now 52.8% of GDP, 6.2 trillion euro. It started the year at 39.4%, or 4.6 trillion euro. The Federal Reserve balance sheet is 32.6% of GDP. Fiscal stimulus is also much smaller than in eurozone economies. The US fiscal impulse is equivalent to 5.2% of GDP, compared to 38% in Germany, 30% in Italy, 23% in France, and 10% in Spain.

The reason why the US economy is improving faster than the eurozone is a more dynamic and flexible labor market with more resilient businesses. That does not take away the important challenges of the US. It lost 7.9 million jobs in hospitality and leisure, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the service sector, which saw the biggest employment reductions, is coming back slowly.

If the United States wants to surprise the world with a much quicker return to record employment it needs to address the permanent job loss figure with tax incentives to hire faster and the continuing jobless claims with a robust and effective set of policies that strengthen business creation and allows existing ones to grow, particularly in digitalization and added-value online services for global customers.

At the current pace, the eurozone will not return to the 2019 employment levels until 2023. In the case of the United States, at the end of 2021 or first quarter of 2022. It is not enough. The global economy may fall back into a recession if the conditions for the labor market and business creation to strengthen are not introduced rapidly.

Governments will have t liberalize the labor market, cut red tape, eliminate harmful overregulation and provide a stable and helpful framework for businesses to start and grow, or they will find themselves in a deeper crisis than feared.